Nepal Faces Rising Wildfire Threat Amid Weak Preparedness

Kathmandu — The dry season has begun, bringing with it the recurring threat of wildfires across Nepal. As winter fades, flames start to engulf forests in the hills, plains, and inner Madhes, turning vast green landscapes into fields of ash.

At times, plumes of smoke rise from nearby forests in the dead of night; other times, a dense gray haze from the Mahabharat range blurs the horizon. Hundreds of forests across the country begin to burn, triggering widespread environmental destruction and severe air pollution.

Statistics reveal that Nepal’s forests are now burning more frequently — and more fiercely — than ever before. The risk of wildfires is increasing, yet the government’s preparedness, policy, and response remain weak. Authorities appear incapable of taking effective measures to confront this escalating disaster.

Experts warn that wildfires are “everyone’s problem — but no one’s responsibility.” Action only begins after the flames erupt; there is little to no effort in prevention or preparedness.

Rising Fire Incidents

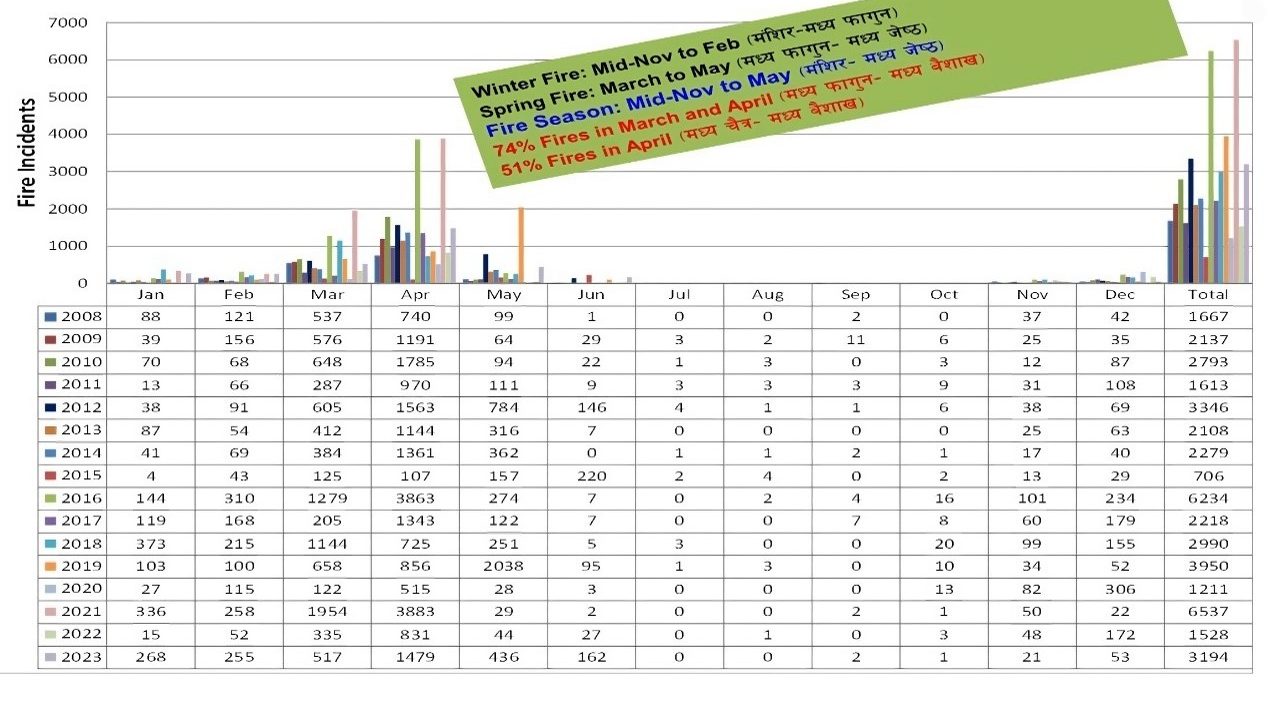

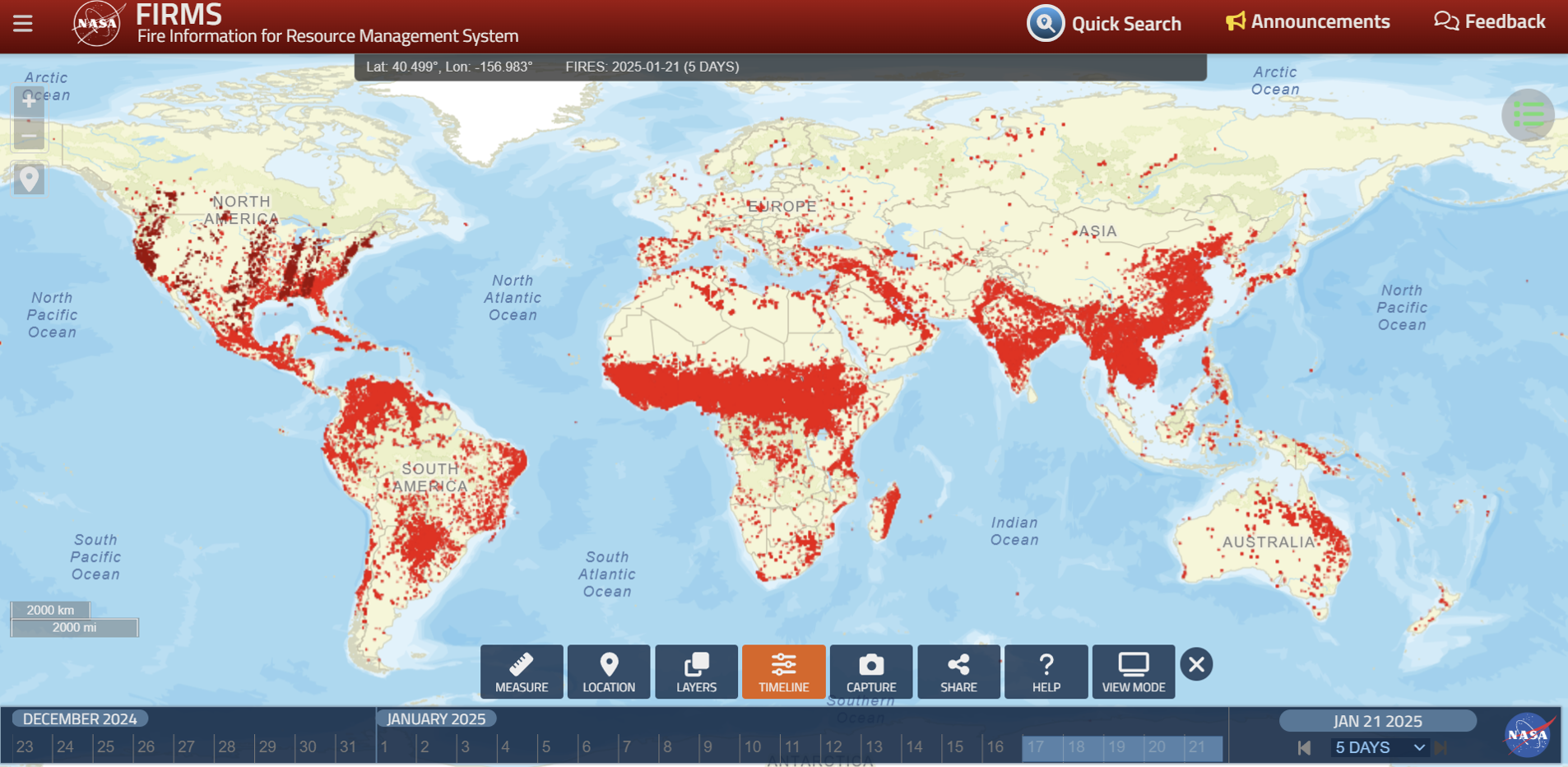

Nepal’s wildfire crisis mirrors similar catastrophic events abroad. In California, recent fires scorched 8,000 acres, displaced 19,000 people, and caused insured losses exceeding 8 billion rupees. In Brazil, 30.8 million hectares burned in 2024 — a 79 percent rise from the previous year.

“Although Nepal’s fires are smaller in scale, their growth rate is alarming,” says forest researcher Smriti Regmi. “Without better fuel management, Nepal could face crises similar to Brazil or Indonesia within the next five years.”

According to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority (NDRRMA), between January 1 and June 25, 2024, 5,125 wildfire incidents were recorded across 74 districts. The previous fiscal year saw 5,171 fire events, killing 110 people, injuring 521, and destroying 1,714 houses and over 2,900 livestock.

Data confirms that wildfires are a persistent and deadly challenge. This is not new — on April 25, 2009, a record 358 wildfires erupted in a single day, killing 49 people, including 13 Nepal Army personnel. Yet, the tragedy failed to spark meaningful change.

In 2016, wildfires damaged 1.3 million hectares of forest, and in 2021, Nepal recorded its highest-ever number — 6,799 fire incidents. Since 2008, the number of wildfires has risen by an average of 12 percent annually, while government response remains slow and outdated.

“Our system still focuses on reaction, not preparation,” says wildfire expert Sundar Sharma, who has long worked with the disaster authority.

A Threat to Livelihoods

Forests cover 45.31 percent of Nepal’s total land area — with 41.69 percent forest and 3.62 percent shrubland. But frequent fires are gradually altering the ecological landscape.

In Gatlang, Rasuwa, a major wildfire in 2004/05 destroyed 500 hectares of forest, burning over 3,100 trees and an estimated 600,000 cubic feet of timber — with total losses exceeding Rs 198 million, according to the Forest Ministry.

“Forests are not just biodiversity reserves; they are the backbone of rural livelihoods,” says environmentalist Sudip Chatkuli. “Wildfires destroy soil fertility, dry up water sources, displace wildlife, and destabilize local economies.”

The issue, therefore, is not only ecological — it directly affects the livelihoods of millions.

Forests Turning Into Powder Kegs

Studies suggest that 95 percent of Nepal’s wildfires are caused by human activity — from discarded cigarette butts and careless herders to campfires and electrical sparks.

Public awareness remains dangerously low. A disaster authority study found that 64 percent of fire personnel lack full knowledge of wildfire causes and long-term effects.

“Our focus is always on where the fire started, not on how the fuel accumulated,” says Sharma. “Dry leaves, branches, and shrubs have turned our forests into gunpowder depots.”

Rural depopulation has worsened the situation — as young people migrate, farmlands lie fallow, and traditional practices of collecting biomass for compost have declined. “What once fed cattle and enriched the soil now lies dead and dry, fueling the next inferno,” Sharma adds.

Poor Preparedness, Limited Equipment

Nepal remains ill-equipped to combat wildfires. The country has only about 200 fire engines, far below international standards, which recommend one firefighter per 20,000 people and one fire engine per 28,000.

Investment in equipment is negligible, and firefighting efforts rely largely on donor support. In 2023–24, the Nepal Army deployed 12,500 soldiers to fight fires in 800 locations — yet tragedies continue, with 13 soldiers killed in Ramechhap (2009) and three in Dolpa (2024).

“Our preparedness is limited to fire trucks and buckets,” admits a forest official. “We need modern tools, trained personnel, and a national strategy.”

Existing technology — portable pumps, wind blowers, and fire retardant sprayers — remains centralized in Kathmandu, leaving rural areas vulnerable.

Toxic Air and Climate Impacts

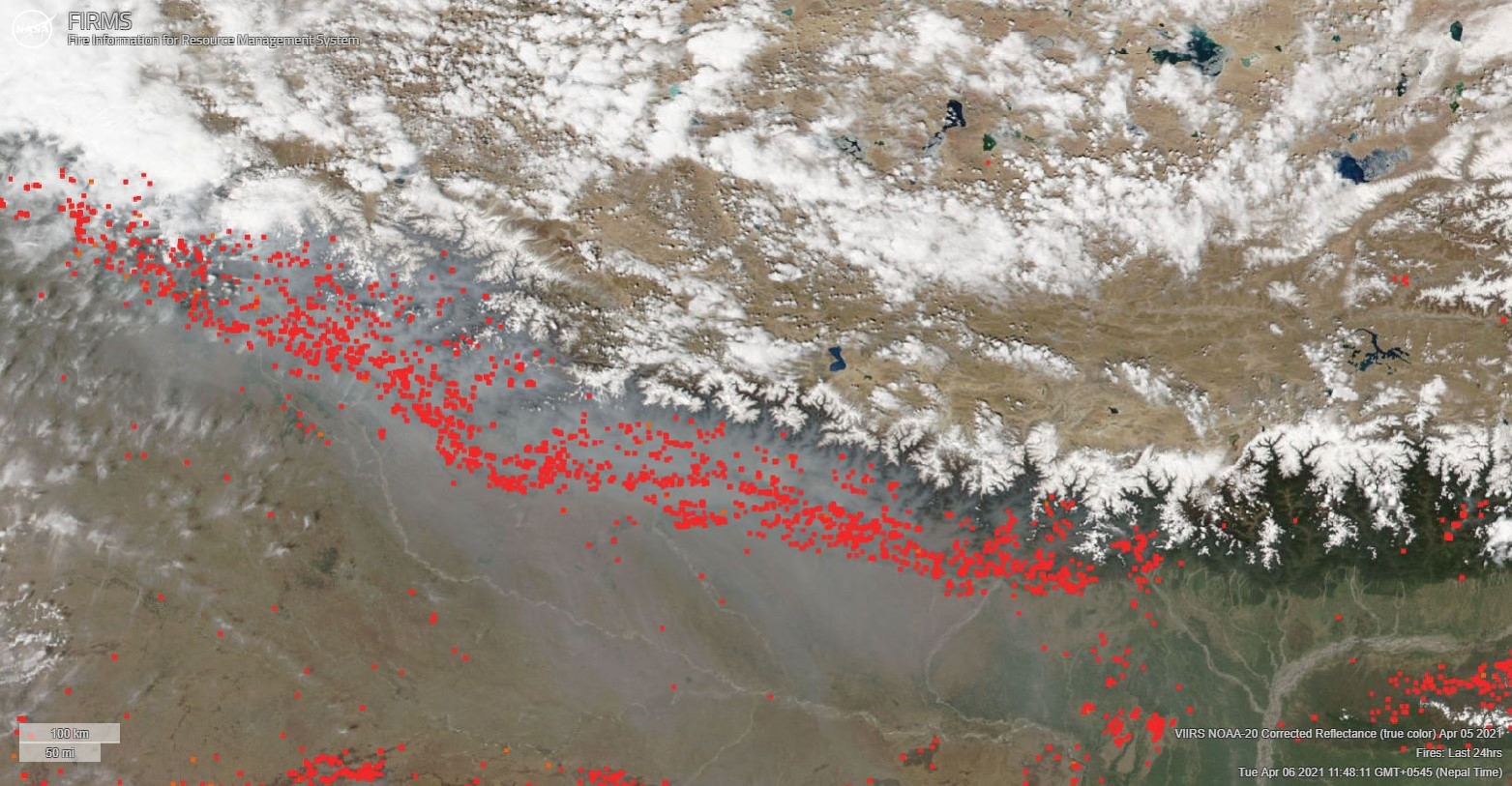

Wildfires not only destroy forests but also worsen air pollution and accelerate climate change. On April 6, 2021, NASA satellite images showed Kathmandu’s air at “hazardous” levels due to hundreds of wildfires nationwide. Schools were closed, flights grounded, and hospitals overwhelmed with respiratory patients.

“The carbon dioxide and black soot from wildfires intensify the greenhouse effect,” warns researcher Smriti Regmi. “They also accelerate glacial melting, raising the risk of glacial lake outbursts — a new form of climate threat for Nepal.”

Globally, wildfires emit an estimated 495 million tons of carbon annually. Nepal, too, faces serious air quality challenges — with over 26,000 deaths each year attributed to air pollution, according to the World Health Organization. The economic toll exceeds 6 percent of Nepal’s GDP.

Smoke and dust from wildfires in neighboring India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh also drift into Nepal, further degrading air quality across the Himalayas.

Institutional Weakness and Policy Gaps

Nepal has numerous legal and policy frameworks addressing wildfires, yet implementation remains minimal. Government documents classify wildfires merely as “natural disasters,” and the Disaster Risk Reduction Act 2017 lists them as “secondary hazards.”

Jurisdiction is fragmented: the Home Ministry treats fires as multi-hazard events, while the Forest Ministry confines them to “forest management issues.”

While strategic plans such as the Forest Fire Management Strategy 2010, Forest Policy 2018, and Disaster Risk Reduction Strategic Action Plan (2018–2030) include slogans about prevention and cooperation, budget allocation is negligible.

In FY 2080/81, the Forest and Environment Ministry spent only 1.8 percent of its Rs 15 billion budget on wildfire risk reduction — more than half of that limited to training and awareness programs.

No dedicated department or regional wildfire control units exist. The Forest Fire Monitoring Cell remains understaffed, and 75 percent of local governments lack any fire prevention plans. Only Bagmati and Gandaki Provinces have adopted partial wildfire policies — both poorly implemented.

The Way Forward

With wildfires now a national emergency, experts urge urgent policy, legal, and institutional reform. Fuel management must be placed at the center of both forest and climate policy.

Dry wood, leaves, shrubs, and undergrowth should be treated as the first layer of risk reduction. Community forest groups can be encouraged to utilize this biomass for bio-briquette, compost, and pellet production, turning risk into resource.

Local governments must be empowered and equipped with modern tools — including helicopters, wind blowers, and portable pumps — supported by GIS mapping and satellite monitoring.

Regular training for security forces, forest technicians, and volunteers is essential. Awareness can also be expanded through media campaigns, mobile alerts, and school programs.

Above all, experts stress, the government must begin to view wildfire management not as an expense, but as an investment in national resilience.

Pitambar Sigdel

Pitambar Sigdel

Feedback