Trump’s new executive order to tear up Obama’s climate policies

- Brad Plumer

This is it. The battle over the future of US climate policy kicks off in earnest Tuesday.

In a sweeping new executive order, President Trump will order his Cabinet to start demolishing a wide array of Obama-era policies on global warming — including emissions rules for power plants, limits on methane leaks, a moratorium on federal coal leasing, and the use of the social cost of carbon to guide government actions.

Everyone knew this was coming: Trump has said repeatedly that he wants to repeal US climate regulations and unshackle the fossil fuel industry. But Tuesday’s order is only a first step. Trump’s administration will now spend years trying to rewrite rules and fend off legal challenges from environmentalists. It’s not clear they’ll always prevail: Some of President Obama’s climate policies may prove harder to uproot than thought.

Trump’s order, meanwhile, doesn’t say anything about whether he wants the US to stay in or withdraw from the Paris climate deal, the key international treaty on global warming. While Trump vowed to pull out of the accord during the campaign, some of his advisers, like Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, have reportedly warned that he’d face immense diplomatic backlash if he did so. A White House official said that’s “still under discussion.”

The order also doesn’t challenge the Environmental Protection Agency’s fundamental authority to regulate greenhouse gases via the so-called “endangerment finding,” a power that Obama used to craft his climate policies after early attempts to pass legislation failed. That’s important: If the EPA’s regulatory authority survives the Trump era, then a future president could use it to write new rules to curb US emissions. That’s what happens when climate policy is crafted through the executive branch, as it currently is in the United States — things can change drastically with a new president.

The key components of Trump’s new climate and energy order

There’s a lot in Trump’s order, so let’s break down its key features. According to White House officials, Trump will tell the EPA and other relevant federal agencies to:

1) Start rolling back the Clean Power Plan. The Clean Power Plan was Obama’s signature climate policy, a major EPA rule aiming to cut emissions from existing US power plants 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. This rule is currently on hold while the DC Circuit Court looks it over, and Trump’s Department of Justice will ask the court to suspend the case until the EPA can review and write a new version of the rule. (It’s unclear if the court will do so; it may still issue an opinion that will influence what can actually be done to rescind or rewrite the plan.)

As I explained at length here, Trump’s new EPA head, Scott Pruitt, will now begin the laborious process of trying to write a new rule — either by insisting that the EPA doesn’t need to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from existing power plants (a legally risky approach) or by replacing Obama’s rule with a more modest version that only requires incremental cuts at coal plants. No matter what approach Pruitt takes, he’ll have to go through the formal rulemaking process, justify the change in court, and survive legal challenges from environmental groups. This could take years to resolve.

2) Reconsider carbon standards for new coal plants. In addition to regulating existing power plants, Obama’s EPA also set CO2 standards for anyone who wants to build a new power plant. The Obama-era standards basically make it impossible to build a new coal-burning facility in the United States unless it can capture its carbon emissions and sequester them underground, a costly and still-nascent technology known as CCS.

By law, Pruitt likely needs to set some sort of standards for new plants, but he could try to rewrite Obama’s rule so that new coal plants merely have to use ultra-supercritical technology, which is less effective at reducing emissions than CCS but is also somewhat cheaper. (Under the Clean Air Act, standards for new plants have to be based on the “best available control technology,” and Pruitt could argue that CCS is not yet widely available.) No matter what approach the EPA takes, however, it’s unlikely utilities will be building many new coal plants soon — especially since natural gas is so cheap.

3) Reconsider regulations on methane emissions from oil and gas operations. Carbon dioxide isn’t the only major greenhouse gas — there’s also methane, a key ingredient in natural gas that can seep into the atmosphere during oil and gas extraction. Obama set a goal of reducing these emissions 40 percent below 2012 levels by 2025, and both the EPA and the Bureau of Land Management set various rules forcing drillers to detect and plug their leaks. The Trump administration may now try to rewrite these rules, though, again, they’ll have to justify any changes through the courts.

4) Revisit the “social cost of carbon” estimate used to justify climate regulations. Back in 2007, a federal judge ordered the Department of Transportation to take climate change into account when weighing the costs and benefits of new regulations.

So in 2009, Obama’s White House gathered a dozen agencies together and tried to assign a dollar value to the cost of emitting a ton of carbon dioxide — taking into account scientific modeling on the damage caused by aspects of global warming, such as droughts and floods. They settled on a central estimate of around $36 per ton in 2015, rising over time. This “social cost of carbon” (SCC) can help justify regulations that reduce emissions — such as the Department of Energy’s efficiency standards for appliances — since there’s a clear way to quantify the benefits.

The Trump administration will now explore ways to redo and possibly lower the SCC estimate, which will make it harder for stringent climate rules to pass cost-benefit analysis — though, again, they may face court challenges. One route they may take: Take into account only the damages that climate change causes the United States, instead of the damage globally. That would produce a smaller SCC. Note, however, that the National Academy of Sciences disagrees with this approach, and many experts think the SCC should be higher, not lower.

5) Lift the moratorium on federal coal leasing. The federal government owns more than 570 million acres of land with coal reserves buried below, which it leases out to mining companies. Environmentalists and other critics have argued that the feds hand out these leases much too cheaply, which amounted to a backdoor taxpayer subsidy to fossil fuels. In 2016, Obama’s Department of Interior put a moratorium on new federal coal leases until they could review and revamp the program.

In his executive order, Trump will tell the Interior Department to lift the moratorium, a fairly straightforward step that can be done with the stroke of a pen. In the short term, this won’t have a huge practical impact, because there’s currently a coal supply glut and mining companies aren’t really pursuing new federal leases right now. The big question is how Trump handles the results of that review, and whether he alters the leasing program to try to get a better deal for taxpayers in the future.

6) Repeal guidance for factoring climate change into NEPA reviews. Under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), federal agencies are supposed to do formal environmental reviews of all major actions they take, like coal leasing or permitting new pipelines. And in many cases, the courts have ordered these agencies to take climate impacts into account. (The agencies don’t necessarily have to do anything to mitigate these impacts, but they do have to account for them and post them publicly.)

Under Obama, the Council on Environmental Quality issued some guidance to the agencies on how to follow these legal guidelines when incorporating climate into their NEPA reviews. Trump is now rescinding this guidance, which can be done with a simple signature.

It’s unclear how much practical impact this will have. Agencies will still be required to follow the law and consider greenhouse gas impacts when conducting environmental reviews of projects like coal leasing, says Michael Burger, executive director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University. If they don’t, they can still get sued in court. If anything, the lack of guidance from Trump’s White House may well cause more confusion around proper procedures to follow — leading to more litigation, not less. What this does signal, though, is that the federal government is going to be a little less diligent about thinking through climate impacts going forward.

7) Rescind a bunch of Obama’s other executive orders on climate. The Obama White House issued a number of other executive orders and documents related to climate change, such as: the Climate Action Plan (basically laying out the administration’s goals on global warming); an order urging federal agencies to reduce their CO2 output; and an order urging federal agencies to help communities strengthen their resilience to climate impacts. Trump can and will undo all of these with a stroke of a pen.

8) Tell agencies to review all rules inhibiting energy production. Finally, under the auspices of promoting “energy independence,” Trump will instruct all federal agencies to review all of their rules, policies, and guidances and see if there’s anything that inhibits the development of domestic energy production — from coal to oil and gas to nuclear power and renewables. In the next 180 days, the agencies will send their findings to the White House, which will decide how to proceed from there.

This executive order is part of a much broader assault on Obama-era climate policies. Earlier this month, Trump announced the EPA would review (and possibly weaken) the Obama’s fuel economy standards for cars and light trucks in the post-2022 period. And the White House is crafting a budget proposal that requests sharp cuts to a variety of climate programs at the EPA, Department of Energy, NASA, NOAA, and elsewhere.

Overturning everything Obama has done on climate will be difficult, however. Some rules, like the fuel economy standards, can only be weakened — not killed entirely. Other regulatory rollbacks may get thwarted by federal judges. And Congress will have final say over the EPA’s budget, with even some Republicans now balking at the steep cuts Trump has been mulling to clean energy programs.

So it’s too soon to say how successful Trump will be in killing all of Obama’s policies — or what the ultimate impact on emissions and global warming will be. But a new research note from the Rhodium Group tries to model what would happen if Trump manages to eviscerate all the climate policies mentioned in Tuesday’s executive order.

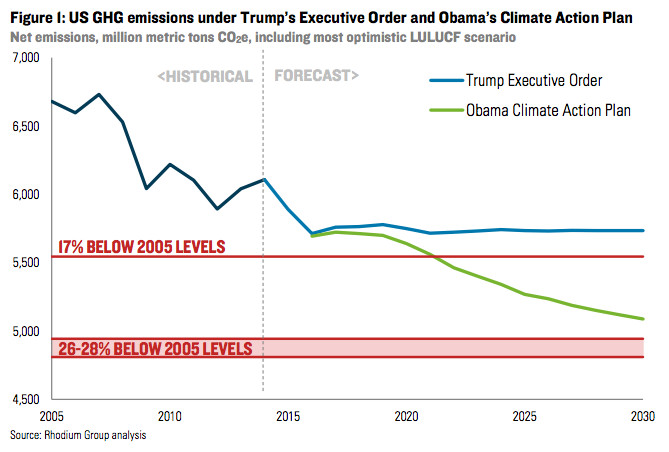

If that happens, the group found, the US is very unlikely to meet its Paris treaty pledge of cutting greenhouse gas emissions 26 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. Instead, emissions would stall out at around 14 percent below 2005 levels — a shallower drop than would’ve been expected if Obama’s policies had remained in place:

What’s notable about this chart is that that Trump’s executive order can’t halt all climate progress. Emissions would still decline gently in the coming years, thanks to market forces and policies that Trump can’t really touch.

For instance: Many US utilities are increasingly moving away from coal and toward cleaner sources such as gas, wind, and solar — that shift will almost certainly continue no matter what the White House does, since it’s being driven by more than EPA rules. And states like New York and California will keep pursuing their own more stringent climate policies.

What Trump can do, however, is halt any momentum that may have been building toward deep decarbonization. If we want to halt climate change, it’s not enough for US emissions to continue to drop slowly or flatline. They have to drop dramatically. That would’ve been a huge challenge even if Hillary Clinton had been elected president — she was mainly planning to expand some of Obama’s EPA programs at the margins. But it now looks extremely unlikely under Trump.

vox.com

Feedback