How Warming Could Impact Your Easter Chocolate

As Easter arrives, children (and adults alike) prepare to chow down on chocolate eggs and nibble chocolate bunnies, ears first, of course. But suppliers and manufacturers of those Easter confections are increasingly worried about how climate change will impact the global supply of chocolate.

Chocolate is produced from cacao bean, which is grown on the cacao tree. These trees have a relatively limited range in which they can grow, between 20 degrees latitude north and south of the Equator. Nearly 70 percent of chocolate production happens in West Africa, in what is known as the cocoa belt, with the other 30 percent split between Asia and the Americas.

Credit: NOAA

“Such an extreme concentration of the production of a commodity in one geographical region makes the global industry highly vulnerable to a regional decline in climatic suitability,” Götz Schroth of Mars Incorporated and the Federal University of Western Pará in Brazil and his co-authors wrote in a 2016 paper that examined how climate change might impact cacao cultivation.

According to the most recent IPCC report, temperatures in West Africa where cacao trees grow are expected to increase 3.8ºF (2.1ºC) by 2050, while no increase in rainfall is expected. For cacao trees, it is that relative lack of rain that has been seen as the biggest threat. In Malaysia, for example, cacao trees already experience the temperatures projected for West Africa in 2050, but West Africa is already susceptible to drought. Higher temperatures without more precipitation could lead to more drought stress via increased rates of evapotranspiration there, especially during the dry season or in the particularly dry conditions that often accompany an El Niño.

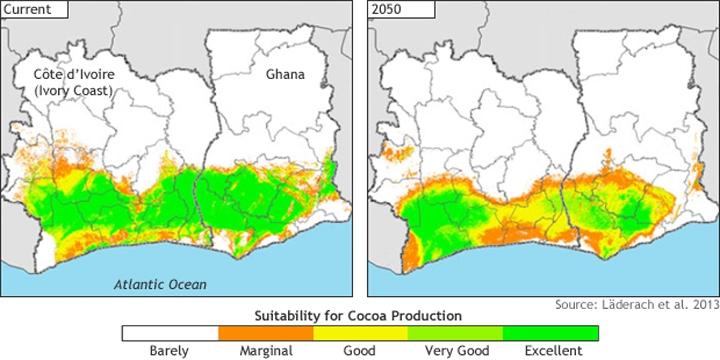

The IPCC report also found that areas suitable for cacao trees may be moving uphill. In Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, for example, climate change could push the optimal growing region up from its current range of 300 to 800 feet above sea level to 1500 to 1600 feet. But this could cause other problems if farmer’s try to move; one area in Ghana at that height is a protected range where agriculture is not permitted.

More recently, Schroth and his colleagues’ 2016 paper looked more specifically at regions of cacao growing in West Africa to see what changes might be in store for climatic suitability for the trees. Overall, things look grim, with most areas where cacao is grown losing up to 20 percent of their current suitability based on 24 climate variables. However, contrary to what previous studies had found, this study says that by 2050, drought stress and the balance between rainfall and evapotranspiration during the dry season should stay around levels already seen in the cocoa belt, with only a few exceptions at the edges of the region.

Instead, the study proposes that the increase in temperatures should be looked at as an important factor for future climatic suitability for chocolate in West Africa. Even though the IPCC projections do not have the cocoa belt reaching the maximum temperatures that cacao trees can withstand by 2050, this projection is for an average year, meaning that locally, temperatures may exceed this limit and damage crops, particularly during warm El Niño years.

While more research will need to be done to continue to determine what will have the most extreme impacts on West Africa’s 2 million cacao farmers, it has been an accepted fact for a while that climate change will negatively impact cacao and that adaptations must be put in place.

Virginia-based Mars, the largest chocolate manufacturer in the world, has taken multiple steps to protect its chocolate supply. Most recently, they were a part of a group of large corporations that spoke out against President Trump’s reversal of climate legislation passed by President Obama.

“We believe the science is clear and unambiguous: climate change is real and human activity is a factor. As a food business, our supply chain and those who work in it are threatened by its impacts,” Edward Hoover, senior manager of corporate communications for Mars, told the Guardian.

And Mars has signaled its desire to help preserve its supply chain and help its farmers adapt. In 2008, Mars launched the Cacao Genome Project, a joint venture with IBM and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to “sequence, assemble and annotate the genome of the cacao tree,” which was then released for free online so that “breeders could begin identifying traits of climate change adaptability, enhanced yield, and efficiency in water and nutrient use,” according to a Mars statement.

In addition to developing more drought resistant seeds, more traditional farming methods could protect cacao trees as well. For example, shading cacao trees with other trees would provide protection from wind and erosion, limit temperatures and evapotranspiration, and provide nutrient-rich leaf litter. The diversification of farming systems with crops and trees that have varying environmental needs has also been proposed as a way to help protect both the crops and the farmers.

Adaptations will necessarily need to differ by region and specific location, as resources vary throughout the West African cocoa belt and the impacts of climate change may vary even within this relatively limited area.

“If progressive climate change affected the climatic suitability for cocoa in West Africa, this would have implications for global cocoa output as well as the national economies and farmer livelihoods, with potential repercussions for forests and natural habitat as cocoa growing regions expand, shrink or shift,” Peter Läderach of the International Center for Tropical Agriculture and colleagues wrote in a 2013 paper.

Climate Central

Julia Langer

Julia Langer

Feedback